SIR ROBERT EDWARD GRANT PRESENTS

Anne Boleyn as the Sitter of Leonardo da Vinci’s La Belle Ferronière: A Hypothetical Reappraisal

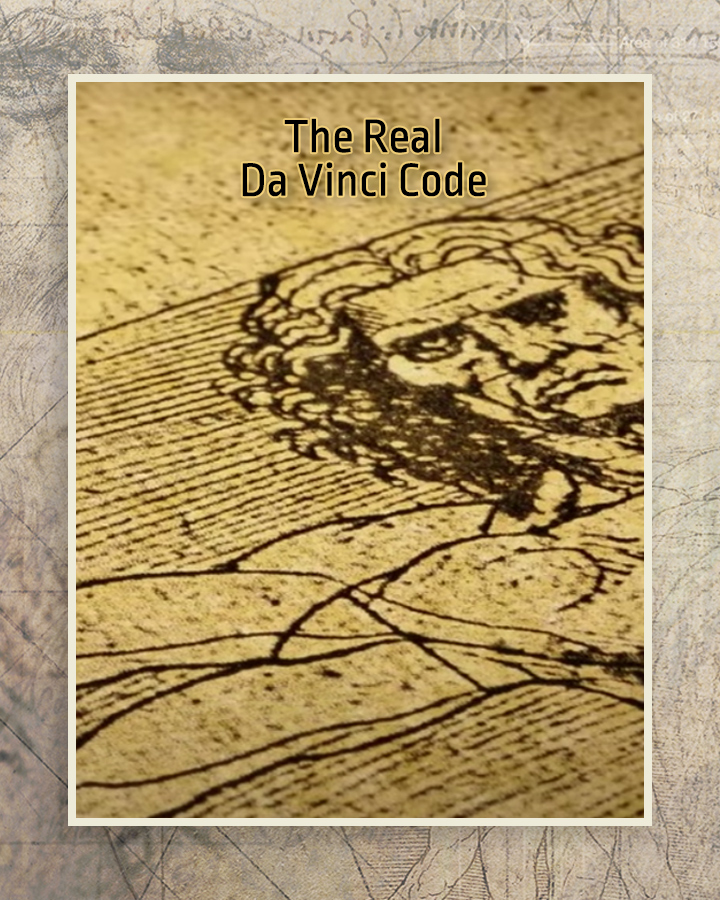

The identity of the sitter in Leonardo da Vinci’s La Belle Ferronière has long been contested. Conventional attribution situates the portrait in Milan during the early 1490s, often linked to Lucrezia Crivelli or another lady of the Sforza court. This essay advances an alternative hypothesis: that the sitter is Anne Boleyn, portrayed during Leonardo’s final years at Amboise (1516–1519). While acknowledging the weight of dendrochronological and stylistic analysis pointing toward the 1490s, I argue that physiognomic concordance, historical context, and the plausible reuse of older panel supports warrant serious reconsideration of Anne Boleyn’s candidacy.

1. Historical Context

Leonardo da Vinci resided at Clos Lucé in Amboise from 1516 until his death in 1519, under the patronage of Francis I. During these years, Anne Boleyn (b. c.1501) was present in France as part of Queen Claude’s household, residing at Amboise and Blois. The convergence of Leonardo and Anne at the French court provides the necessary precondition for portraiture.

2. Physiognomic Evidence

Direct comparison between La Belle Ferronière and later Tudor portraits of Anne Boleyn reveals strong consistencies in facial structure: the elongated oval face, straight nose, delicate chin, central hair part, and distinctive lip formation. These traits are unusual enough in their precise configuration to suggest continuity between depictions of a young Anne in France and a mature queen in England.

3. The Question of Panel Dating

Dendrochronology has dated the oak support of La Belle Ferronière to the late 15th century. This aligns neatly with a Milanese dating. Yet, seasoned panels were highly prized for their stability and were often preserved for extended periods. Leonardo, whose working practices included revisiting earlier projects across decades, could have retained or re-employed such a panel for a French-period portrait. The assumption that Leonardo invariably painted on freshly prepared panels may reflect modern expectations more than Renaissance practice.

4. Stylistic Reversion

The portrait’s sharp contours and sculptural clarity echo Leonardo’s Milanese work of the 1490s. However, Leonardo was not bound by linear stylistic progression. He frequently reused compositional types and reverted to earlier modes of representation. In the case of Anne Boleyn, Leonardo may have chosen a crisper idiom to emphasize youthful precision rather than the atmospheric sfumato of his late devotional works.

5. Title and Misidentification

The name “La Belle Ferronière” appears only in 17th-century French inventories, where it was mistakenly linked to a mistress of Francis I. More literally, the term refers to the jeweled forehead band (ferronnière) the sitter wears. If the sitter were Anne Boleyn, posthumous French inventories may have deliberately obscured her identity. Following her execution in 1536, a connection to a disgraced English queen would have been politically inconvenient.

6. Political Significance

A portrait of Anne Boleyn by Leonardo would have served a dual function at the French court: displaying Francis I’s cultural prestige and reinforcing Anglo-French ties through the depiction of an English noblewoman. Such a painting could have accompanied Anne to England, shaping perceptions of her beauty long before Holbein’s images fixed her visual identity in the English imagination.

Conclusion

The Milanese dating of La Belle Ferronière remains well-supported by scientific analysis and stylistic congruence. Nevertheless, the hypothesis of Anne Boleyn as the sitter offers an alternative framework that merits exploration. The confluence of Leonardo and Anne at Amboise, the physiognomic match across decades, the plausible reuse of an older panel, and the later misdirection of the painting’s title together open the door to reconsideration. Rather than dismissing the possibility outright, art history benefits from entertaining such reappraisals, which challenge established narratives and broaden our understanding of Renaissance portraiture.

Author: Sir Robert Edward Grant

Resources

Learning Materials

Elements offered to continue your learning of the 24 precepts. Dive into Code X or read one of Robert's many books to enliven your mind.